Fiabe di carta e inchiostro si inchinano davanti a coni rovesciati della città scolpita. E ne disegnano la nobiltà. Precipitata nella miseria e poi risorta. Matera, vergogna nazionale nel secondo dopoguerra, con le sue case rupestri abbandonate alla rovina, risale lentamente dall’abisso e si trasforma in regina, svelando la luce ritrovata dei suoi gioielli.

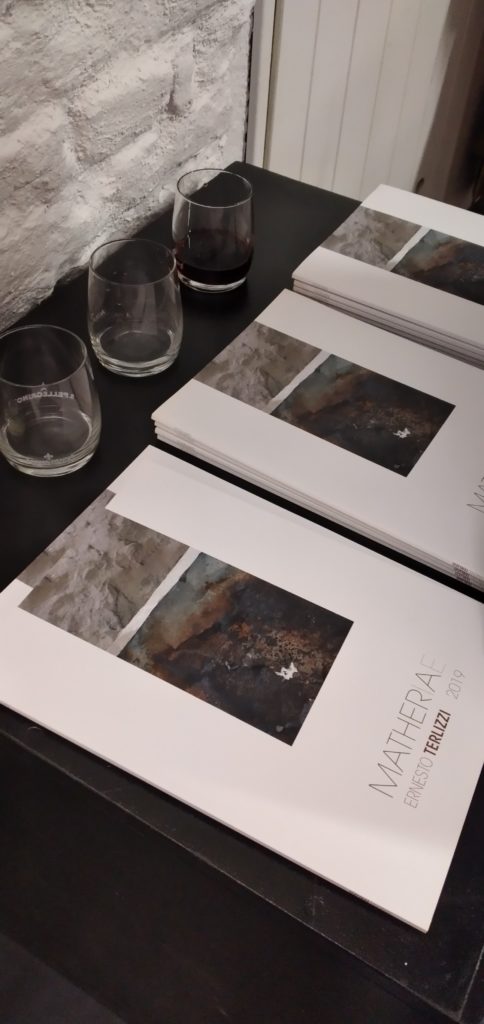

Quei sassi, che narrano storia, cultura e bellezza, si offrono come Matheriae d’arte al salernitano Ernesto Terlizzi che li reinventa nelle proprie opere. Visioni che evocano vita quotidiana, tradizioni e memoria attraverso merletti, china, latta, piume.

dell’antica capitale polacca

Stratificazioni di vita narrate e raccolte in una mostra che dalla capitale della cultura del 2019, passando per la pinacoteca provinciale di Salerno, arriva il 13 settembre all’istituto italiano di cultura di Cracovia dove il fascino abbraccia antichità e splendore. E qui resterà aperta al pubblico fino al 4 ottobre.

Quello che era una volta il sotterraneo della palazzina di 4 piani da dove si diffondono la voce e la cultura d’Italia, tra luci di oggi e pietre del passato, si rivela, nella sua essenzialità, spazio ideale per accogliere lavori che sembrano invitare chi guarda a toccarli. Sino sentirne le vibrazioni ispirate da un microcosmo di storie e sentimenti.

In un tardo pomeriggio d’inizio weekend, che minaccia pioggia intensa e annuncia inondazioni in Polonia per il giorno successivo (sabato), immaginare un pubblico numeroso, attento e entusiasta è davvero audace. Ma l’amore (per l’Italia) trionfa su tutto e alla spicciolata arrivano tante persone pronte ad ascoltare l’artista atterrato con un volo da Napoli poche ore prima, per partecipare all’inaugurazione.

Accanto a lui, il giovane e dinamico direttore dell’Istituto Matteo Ogliari che ha ereditato questa esposizione, rinviata per il Covid, dal precedente, Ugo Rufino, (anche lui presente, artefice di un primo percorso espositivo di Terlizzi a Cracovia nel 2018), e lo storico dell’arte Alberto Dambruoso che ne è curatore. Li affianca una giovane italianista, Hanna Kulińska, appena laureata, che ha l’impegnativo compito di tradurre.

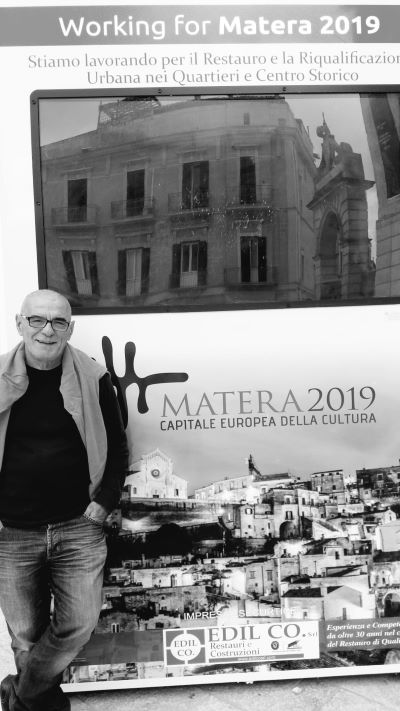

Uomo del Sud, sulla scena artistica italiana da oltre quarant’anni, Ernesto spiega che Matera per lui è una folgorazione cominciata dopo aver letto Cristo si è fermato a Eboli di Carlo Levi. Che a proposito

a Cracovia

della città perduta scriveva «Io guardavo passando, e vedevo l’interno delle grotte, che non prendono altra luce e aria se non dalla porta. Alcune non hanno neppure quella: si entra dall’alto, attraverso botole e scalette… Sul pavimento stavano sdraiati i cani, le pecore, le capre, i maiali. Ogni famiglia ha, in genere, una sola di quelle grotte per tutta abitazione e ci dormono tutti insieme, uomini, donne, bambini e bestie. Così vivono ventimila persone».

Nel 1970, durante il primo incarico di docente a Lauria, in provincia di Potenza, Terlizzi va, nel capoluogo lucano, alla presentazione di un libro dello scrittore con cui s’intrattiene brevemente, conservando nel cuore la povertà infinita da lui descritta. Finché negli anni duemila, in televisione, non vede riapparire quei sassi in una fulgida dimensione: diamanti della prossima capitale italiana della cultura.

E allora non resiste alla tentazione artistica di viverci per una settimana, lasciandosi avvolgere da un intreccio di architettura e roccia. Così nascono le sue fiabe di carta che adesso incontrano la magia di Cracovia, antica capitale di un paese dove l’Italia è compagna di strada millenaria. E che suggeriscono a chi visita la mostra di volare a Matera per ammirarli.

Di questa amicizia, suggellata sull’orma del cristianesimo, ci sono tracce disseminate ovunque, innanzitutto nel Castello sulla riva sinistra del fiume Vistola e nell’adiacente cattedrale che si possono raggiungere in pochi minuti dall’istituto di via Grodzka.

Il castello acquisisce tratti rinascimentali grazie a Bona Sforza, figlia del duca di Milano Gian Galeazzo e di Isabella d’Aragona.

Ha 24 anni quando, nel 1518, va a nozze con il cinquantunenne (e vedovo) Sigismondo, per procura a Napoli. Divenuta regina consorte, chiamerà a corte artisti e architetti italiani. Ma trasformerà anche la cucina della sua nuova terra, inserendo le verdure coltivate nei giardini reali.

Quando la capitale viene trasferita a Varsavia, la fantasia dei nostri architetti contribuisce a renderla grandiosa, mentre gli aristocratici h già inviano da tempo i loro rampolli alla gloriosa università di Padova. E poi c’è la leggenda del babà (napoletano) in 2 versioni pittoresche, con unico protagonista, Stanislao, ultimo sovrano polacco.

Fuggiasco in Francia, ospite della figlia che ne ha sposato il re, goloso ma sdentato, Stanislao suggerisce al pasticciere un dolce morbido e liquoroso. L’altra leggenda, invece, è quella che lo vede infuriato scagliarlo (perché non gradito) contro una bottiglia di rum che avrebbe finito per inzupparlo. Il risultato è delizioso e i maestri chef d’oltralpe, in seguito, lo faranno conoscere nel regno di Napoli. Ma il babka ponczowa originario esiste ancora in Polonia: è una specialità pasquale dalla forma di pandoro.

Sono alcuni degli aneddoti raccontati a chi scrive questo articolo da Magdalena Wrana, docente di lingua e letteratura italiana all’università Jagellonica di Cracovia, ora a Napoli per 3 mesi, dopo aver vinto un concorso (con una collega italiana) dell’ateneo campano Luigi Vanvitelli.

Magda (così la chiamano gli amici) vive con un piede tra Napoli e Cracovia e assiste, nella sua funzione, la console onoraria Katarzyna Likus: è il suo modo di restituire all’Italia tutto l’amore che vi ha sempre ricenuto. E all’ apertura di “Matheriae”, dove osserva con orgoglio il successo (applaudito) della sua ex allieva traduttrice, è rapita dai lavori di Terlizzi che confermano la sua passione per la cultura mediterranea sviluppata grazie a un’infanzia trascorsa in Libia.

Italia e Polonia, un legame magico che colpisce al suo arrivo, quasi due anni fa, anche il direttore Matteo Ogliari: in tanti (e sono sempre più numerosi) s’iscrivono ai corsi raggiungendo livelli linguistici sorprendenti.

Una complicità culturale che esplode in una scintilla ardente: il capolavoro di Leonardo, La Dama con l’ermellino, gemma d’arte incastonata tra le altre bellezze del museo Museo Czartoryski, nel centro storico di Cracovia, dove domina l’immensa piazza del Mercato. Il fiato resta sospeso e l’incantesimo continua ad affascinare il mondo.

©Riproduzione riservata

Per saperne di più

https://iiccracovia.esteri.it/it/

Cracow/ Italian cultural Institute: Ernesto Terlizzi tells the story of the Sassi of Matera in paper tales. The (magical) link between our country and Poland

Tales of paper and ink bow to the inverted cones of the sculpted city. And they portray its nobility. Plunged into misery and then resurrected. Matera, a national disgrace after the Second World War, with its rupestrian houses abandoned to ruin, slowly rises from the abyss and becomes queen, revealing the newfound light of its jewels.

These stones, which tell of history, culture and beauty, offer themselves as material for art to Ernesto Terlizzi, born in Salerno, who reinvents them in his own works. Visions that evoke everyday life, traditions and memories through lace, ink, pewter and feathers.

Layers of life told and collected in an exhibition that arrives from the Capital of Culture 2019, via the Provincial Picture Gallery of Salerno, on September 13th at the Italian Institute of Culture in Krakow, where fascination embraces antiquity and splendor. The exhibition will be open to the public until October 4th.

What was once the basement of the four-storey building from which the voice and culture of Italy spread, between the lights of today and the stones of the past, turns out to be, in its essence, an ideal space to host works that seem to invite the viewer to touch them. Even to feel the vibrations inspired by a microcosm of stories and emotions.

On a late afternoon at the beginning of the weekend, with the threat of heavy rain and the announcement of floods in Poland for the next day (Saturday), it is indeed audacious to imagine a large, attentive and enthusiastic audience. But love (for Italy) triumphs over all, and in a flash many people arrive, ready to listen to the artist who arrived a few hours earlier on a flight from Naples to attend the opening.

At his side is the young and dynamic director of the Institute, Matteo Ogliari, who inherited this exhibition, postponed for Covid, from his predecessor, Ugo Rufino (also present, the creator of an early Terlizzi exhibition in Krakow in 2018), and the art historian Alberto Dambruoso, who is its curator. They are joined by a young Italianist, Hanna Kulińska, a recent graduate, who has the challenging task of translating.

Ernesto, a man from the south who has been on the Italian art scene for more than forty years, explains that Matera is a thunderbolt for him after reading Carlo Levi’s Christ Stopped at Eboli. Who wrote about te lost city: I looked as I passed by and saw the inside of the caves, which only let in light and air through the door. Some do not even have that: one enters from above, through trapdoors and ladders…. Dogs, sheep, goats and pigs lie on the floor. Each family usually has only one of these caves for the whole dwelling, and they all sleep there together, men, women, children, and animals. Twenty thousand people live this way.

In 1970, during his first teaching assignment in Lauria, in the province of Potenza, Terlizzi went to the presentation of a book by the writer in the Lucanian main city, with whom he spoke briefly, keeping in his heart the infinite poverty he described. Until in the 2000s, on television, he saw those stones reappear in a shining dimension: diamonds of the next Italian Capital of Culture.

And so he could not resist the artistic temptation to live there for a week, to be surrounded by an interweaving of architecture and stone. This is how his paper fairy tales were born, which now meet the magic of Krakow, the ancient capital of a country where Italy is a millennial companion. And that suggest to the visitors of the exhibition to fly to Matera to admire them.

Traces of this friendship, sealed in the footsteps of Christianity, are scattered everywhere, especially in the castle on the left bank of the Vistula River and in the adjacent cathedral, which can be reached in a few minutes from the institution at Grodzka Street.

The castle acquired Renaissance features thanks to Bona Sforza, daughter of the Duke of Milan Gian Galeazzo and Isabella of Aragon.

She was 24 years old when she married the 51-year-old (and widower) Sigismondo by procuration in Naples in 1518. As queen consort, she would invite Italian artists and architects to her court. But she would also transform the cuisine of her new land, incorporating vegetables grown in the royal gardens.

When the capital is moved to Warsaw, the imagination of our architects helps to make it great, while aristocrats already send their offspring to the glorious University of Padua. And then there is the legend of the Baba (Neapolitan) in 2 picturesque versions, with the only protagonist Stanislaus, the last Polish king.

A refugee in France in the eighteenth century, a guest of the daughter who married its king, gluttonous but toothless, Stanislaus proposed to the patissier a soft, liqueur-like dessert. According to another legend, he angrily threw it (because he did not like it) into a bottle of rum, which ended up soaking it. The result was so delicious that master chefs from across the Alps later made it famous in the Kingdom of Naples. But the original babka ponczowa still exists in Poland: it is an Easter specialty in the shape of a pandoro.

These are some of the anecdotes told to the author of this article by Magdalena Wrana, Professor of Italian Language and Literature at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow, who is now in Naples for three months after winning a scholarship (with an Italian colleague) at the Luigi Vanvitelli University of Campania.

Magda (as her friends call her) lives with one foot between Naples and Krakow, assisting Honorary Consul Katarzyna Likus in her function: it’s her way of giving back to Italy all the love she has always received there. And at the opening of “Matheriae”, where she proudly observes the (applauded) success of her former student translator, she is enchanted by Terlizzi’s works, which confirm her passion for Mediterranean culture, developed through a childhood spent in Libya.

Italy and Poland, a magical bond that strikes on his arrival, almost two years ago, even the director Matteo Ogliari: many (and they are more and more numerous) register in the courses, reaching surprising linguistic levels.

A cultural complicity that explodes into a flaming spark: Leonardo’s masterpiece, the Lady with the ermine, a jewel of art set among the other beauties of the Czartoryski Museum in Krakow’s Old Town, where the immense Market Square dpminates. The breath is suspended and the magic continues to fascinate the world.

Learn more at

https://iiccracovia.esteri.it/it/

.