Nuenen, aprile 1885

Litografia su carta velina, 28,4×34,1 cm

© Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The

Netherlands

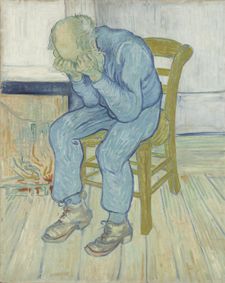

Vecchio disperato (Alle porte dell’eternità)

Saint–Rémy, maggio 1890

Olio su tela, 81,8×65,5 cm

© Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The

Netherland

La normalità è una strada comoda per camminare ma non vi cresce nessun fiore. Vincent Willem lo sapeva bene, per questo non la scelse mai come traccia di vita. Lui, nato nel 1853, a Groot Zudert, nel nord Brabante, in Olanda, primo di sei figli del pastore protestante Tehodorus e di Anna Carbentus, si lanciò in un tortuoso labirinto esistenziale che lo condusse dai chiaroscuri dei mangiatori di patate alla brillantezza dei suoi girasoli e alla disperata luce del vecchio seduto su una sedia alle porte dell’eternità, dipinto quando ormai il suo cuore è schiacciato da un oscuro e inesorabile peso.

Il 27 luglio 1890, a Auvers-sur-Oise in Francia, si spara al petto in mezzo un campo di grano: resta ferito e pensa di aver tradito sé stesso facendo cilecca. Morirà, invece, dopo due giorni di agonia. Non è ancora il celebre Van Gogh, ma lascia una scia di commozione e dolore. Innanzitutto nell’anima del fratello Theo, mercante d’arte, già malato, con cui aveva un legame fortissimo e che per questo sofferenza si aggraverà, spegnendosi sei mesi più tardi.

Dal dramma familiare, comincia il fulgido destino d’arte di Vincent, affidato soprattutto a due donne. La prima è la giovane cognata Johanna Bonger, rimasta vedova con un bambino di pochi mesi che ha il nome dello zio.

Grazie al proprio intuito manageriale, Jo riuscirà a intessere rapporti con pittori, intellettuali, scrittori per divulgare quel patrimonio di opere e lettere che affollavano l’appartamento in cui abitava con Theo, coordinando mostre nelle città dei Paesi Bassi. E pubblicando, infine, le lettere in olandese e tedesco, traducendole in buona parte pure in inglese, passando. poi, alla sua scomparsa, il testimone al figlio Vincent Willem che creerà la Fondazione Vincent Van Gogh e firmerà un accordo con lo Stato per far sorgere il Museo di Amsterdam, aperto nel 1975.

Helene Kröller-Müller è l’altra figura femminile che gli rende giustizia. Lei stessa artista, ne riconobbe il genio, sentendosi affine alla sua vicenda umana e irresistibilmente attratta dalla sua attenzione per gli ultimi. Ricca per famiglia (di industriali tedeschi) e matrimonio (olandese) con l’imprenditore Anton Kröller, si avvicinò all’arte attraverso l’insegnante della figlia, Henk Bremmer e rimase folgorata da Van Gogh anche se i loro percorsi non si incrociarono mai.

Divenne una febbrile collezionista: non solo opere di Van Gogh, ma anche di Picasso, Gris, Mondrian, Signac, Seurat, Redon. Sognando per anni di costruire un museo che potesse essere custode di quella bellezza.

Non fu facile, perché nonostante fosse già chiaro nella sua mente il progetto di erigerlo nella grande riserva naturale che possedeva nei Paesi Bassi orientali, the Hoge Veluwe, dovette annullarlo nel 1921, quando l’azienda famigliare si trovò sull’orlo della bancarotta. Un periodo di crisi che non le impedì, tuttavia, di far circolare in esposizioni europee ma anche negli Stati Uniti, i quadri di Vincent, finché non riuscì a realizzarlo grazie alla partecipazione dello stato olandese. Nel 1938 quella che sembrava un’utopia diventò realtà: Hellene stesse ne diventò la direttrice.

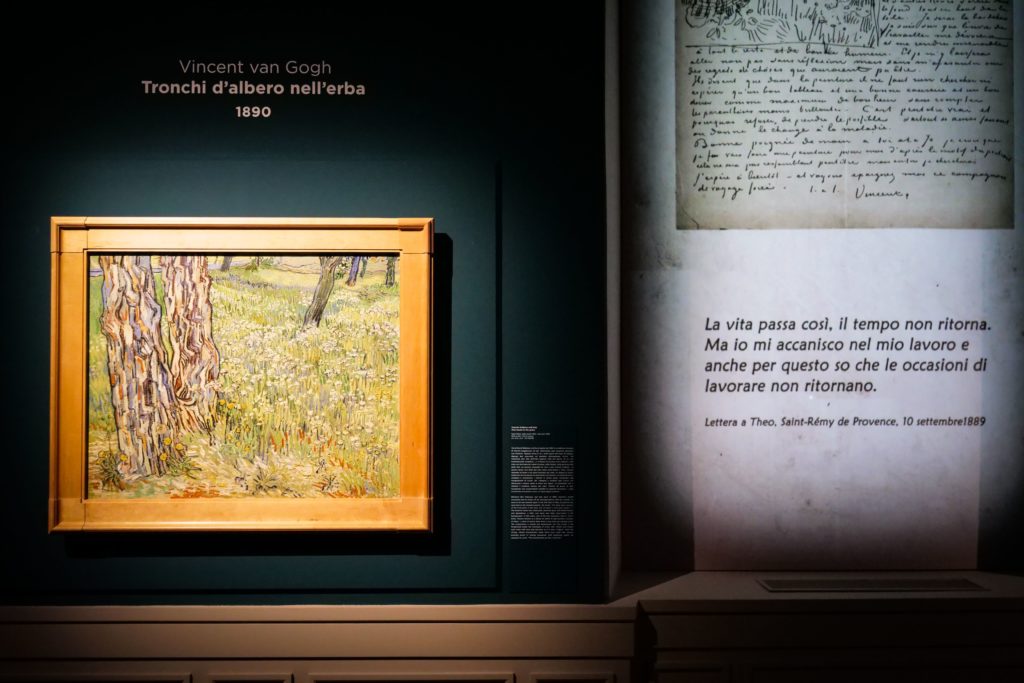

Ed è da questo museo che provengono oltre 50 capolavori proposti per la mostra di Van Gogh, a Palazzo Bonaparte, in piazza Venezia, curata da Maria Teresa Benedetti e Francesca Villanti, organizzata da Arthemisia.

Aperta in ottobre, l’esposizione è stata prorogata fino al 7 maggio per l’incessante afflusso di pubblico che impone lunghe file e tanta pazienza d’attesa, malgrado l’orario prolungato fino a mezzanotte.

Il percorso inizia da sei magnifici pezzi della collezione olandese, nati in epoche diverse, firmati da Lucas Cranach il Vecchio, Henri Fantin-Latour, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Floris Verster, Paul Gauguin e Pablo Picasso. Meraviglie che annunciano i passi del genio, quasi sconosciuto prima della sua tragica fine. Seguono le 4 sezioni dedicate alla produzione di Vincent: divise tra Olanda, Parigi, Arles, infine, –Saint-Rémy-de-Provence e Auvers-sur-Oise.

Luci soffuse, crepuscolari, struggenti accompagnano, tra due piani dell’edificio, il tormento della traversata di Van Gogh sul pianeta Terra, ripiegato com’era nella propria dimensione interiore: anche le scolaresche accompagnate dalla guida a scoprire particolari dei suoi dipinti restano affascinate da un itinerario artistico che volge alla follia, partendo dalle tenebre di un autodidatta attento alla quotidianità dei lavoratori (zappatori, seminatori aratori di entrambi i sessi, ecco ecco ciò che devo disegnare di continuo, scriveva al fratello Theo. Devo osservare e disegnare tutto quel che appartiene alla vita d campagna…) per raggiungere, infine, un’esplosione di colori abbaglianti, dal soggiorno a Parigi in poi fino al suicidio. Ma la figura umana non abbandonerà mai la sua pittura.

Arles, 17 – 28 giugno 1888 ca

Olio su tela, 64,2×80,3 cm

© Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The

Netherland

Quanto sbaglia l’uomo che non si considera piccolo, che non si rende conto di non essere che un atomo. Che lui si sentisse così gli era ben chiaro sin dalla vita trascorsa in una famiglia dove pensava di essere definito un reietto dal padre in particolare che non accettava la dimensione totalizzante della fede percepita da Vincent. C’è in casa una tale ripugnanza nei miei confronti, come se fosse entrato un grosso cane ispido. Magari entrerebbe nella stanza con le zampe bagnate – e poi è così ispido. Darà fastidio a tutti. E abbaia così forte.

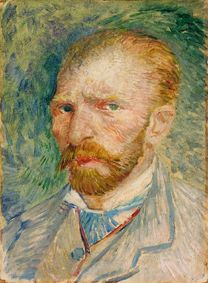

Autoritratto, Parigi, aprile – giugno 1887

Olio su cartone, cm 32,8×24

© Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The

Netherlands

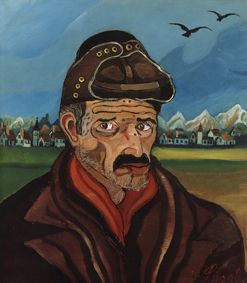

La sua è una solitudine dilatata nello spazio dei giorni e incontra idealmente, in una sala dell’esposizione, quella di uno dei più grandi protagonisti dell’arte italiana del Novecento, Antonio Ligabue (Zurigo, 18 dicembre 1899 – Gualtieri, 27 maggio 1965 ), anche lui smarrito nella fragilità della propria esistenza: un confronto emozionante tra autoritratti di due persone spiritualmente e tecnicamente lontane, accomunate, però, dall’esigenza di riprodurre in modo quasi ossessivo la propria immagine, in un mondo che le relegava ai margini.

1954-55, collezione privata

Olanda, Anversa dove studia la grandiosità di Rubens, la Francia. Ma anche Londra (più esattamente Ramsgate). Vincent osserva, viaggia, cammina. Nella continua ricerca di un senso moderno del colore, dalle pennellate nervose a quelle più morbide. Illuminante l’incontro parigino nel 1886 con gli impressionisti e soprattutto con i puntinisti, Signac e Seraut che dipingevano attraverso una scomposizione cromatica in piccoli punti.

L’arte è un processo complesso, una sofferenza enorme. Vincent è caparbio e non è abituato a sottomettersi. Insegue sé stesso, e va oltre l’esperienza parigina. Ecco Arles, con la campagna e la casa gialla dove invita l’amico Paul Gaugin. Ma i rapporti tra i due si lacerano. Secondo la versione di Gaugin, Vincent cerca di colpirlo con il rasoio e lui si allontana spaventato. Con quella lama affilata, Van Gogh si taglierà una parte dell’orecchio sinistro.

Lavora con intensità persino quando decide da solo di entrare nel manicomio di Saint-Rémy-de-Provence ma le allucinazioni sono in agguato e non gli resta che la pittura per esprimere la tristezza delle ultime ore ricostruite attraverso i quadri allineati nella intensa atmosfera di Palazzo Bonaparte.

Vincent tiene per mano chi scrive questa cronaca d’arte anche il giorno successivo, a pochi passi dal Museo nazionale archeologico, nella seicentesca chiesa di San Potito a Napoli, dove, per celebrare i 170 anni dalla nascita di Van Gogh, proprio come nella capitale, è in corso fino al 30 aprile Van Gogh: the immersive experience.

Una sontuosa realtà virtuale che ha già incantato il pubblico di Belgio (Bruxelles), Cina (Pechino e Hanghzou), Israele, Inghilterra (Londra, York e Leicester), Stati Uniti (New York e Washington)e ugualmente i napoletani nella versione allestita l’anno scorso a Palazzo Fondi e adesso ampliata nella struttura che appartenne alle monache benedettine.

Mamme con bambini, giovani coppie, adolescenti, studentesse e studenti universitari: è un viavai continuo su prenotazione. Prima di farsi sommergere dalle emozioni proiettate sulle pareti tra musica e la voce di un Van Gogh redivivo all’accento british che rievoca frasi tratte dal carteggio con Theo, un documentario illustra l’outsider Van Gogh mentre in un altro angolo espositivo riappare fedelmente ricostruita la stanza di Arles da lui stesso immortalata nell’olio su tela del 1888 e ripresa in altre varianti, simbolo di un luogo protetto dalle turbolenze esterne.

Una tempesta d’arte da assorbire a occhi spalancati su sedie a sdraio, panchine e morbici cuscini: i girasoli, la notte stellata, il campo di grano con corvi, i fiori di iris dalle sfumature viola e il suo volto che rimbalza a ritmo serrato tutt’intorno. Il pubblico è rapito da una girandola di visioni.

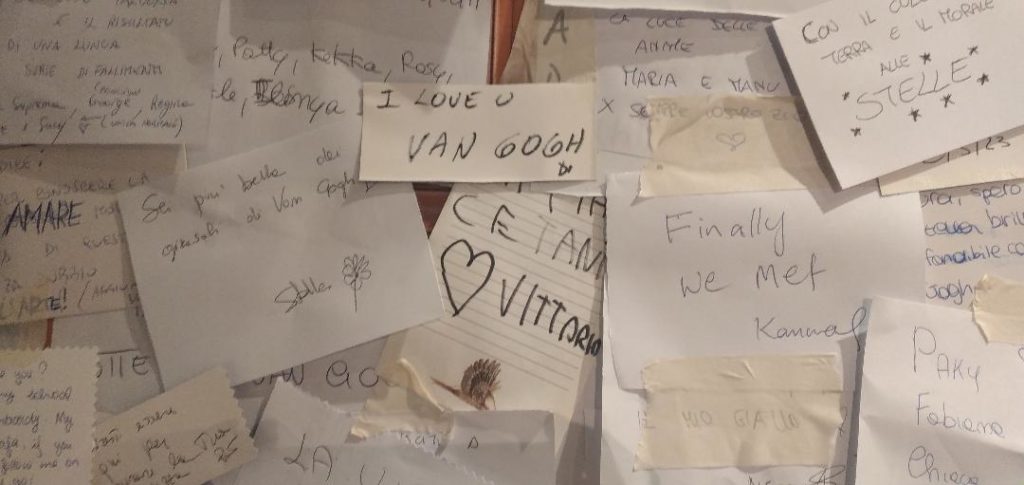

All’uscita tanti biglietti del pubblico per raccontare le ore passate con l’artista. Uno su tutti riassume l’entusiasmo in 5 parole: Van Gogh I love you. Confermando il profetico pensiero di Camille Pissarro, uno dei maggiori esponenti dell’impressionismo: Costui o diventerà pazzo, o ci farà mangiare la polvere a tutti quanti. Se poi farà l’uno e l’altro non sono in grado di prevederlo.

©Riproduzione riservata

LA MOSTRA A ROMA

Palazzo Bonaparte,

Piazza Venezia

VAN GOGH

Capolavori dal Kröller-Müller Museum

Prorogata fino al 7 maggio 2023

LA MOSTRA A NAPOLI

Van Gogh

L’esperienza immersiva

fino al 20 aprile

Chiesa di San Potito, via Tommasi,1

The exhibitions in Rome and Naples/ Vincent Van Gogh: “How wrong is the man who does not realize that he is but an atom.” That shining destiny of art, after the suicide

Normality is a comfortable road to walk but no flowers grow there. Vincent Willem knew this well, which is why he never chose it as his life track. He, born in 1853, in Groot Zudert, North Brabant, Holland, the first of six children of the Protestant pastor Tehodorus and Anna Carbentus, launched himself into a tortuous existential labyrinth that led him from the chiaroscuros of the potato eaters to the brilliance of his sunflowers and the desperate light of the old man sitting in a chair at the gates of eternity, painted when by then his heart was crushed by a dark and inexorable weight.

On July 27, 1890, in Auvers-sur-Oise, France, he shot himself in the chest in the middle of a wheat field: he was wounded and thought he had betrayed himself by making a misfire. Instead, he would die after two days of agony. He is not yet the celebrated Van Gogh, but he left a trace of emotion and grief. First of all in the soul of his brother Theo, an art dealer, already ill, with whom he had a very strong bond and who will be aggravated by this suffering, passing away six months later.

From the family drama, begins Vincent’s shining destiny of art, entrusted mainly to two women. The first is his young sister-in-law Johanna Bonger, widowed with a baby just a few months old named after her uncle.

Thanks to her managerial intuition, Jo will manage to weave relationships with painters, intellectuals, writers to popularize that heritage of works and letters that crowded the apartment where she lived with Theo, coordinating exhibitions in Dutch cities. And by publishing, finally, the letters in Dutch and German, translating a good part of them into English as well, passing. then, upon his death, the baton to his son Vincent Willem who would create the Vincent Van Gogh Foundation and sign an agreement with the state to raise the Amsterdam Museum, which opened in 1975.

Helene Kröller-Müller is the other female figure who would do him justice. An artist herself, she recognized his genius, feeling a connection to his human story and irresistibly attracted by his concern for the underdogs. Wealthy by family (of German industrialists) and marriage (Dutch) to entrepreneur Anton Kröller, she approached art through her daughter’s teacher, Henk Bremmer, and was thunderstruck by Van Gogh even though their paths never crossed.

She became a feverish collector: not only works by Van Gogh, but also by Picasso, Gris, Mondrian, Signac, Seurat, Redon and, of course, Van Gogh. She dreamed for years of building a museum that could be its custodian.

It was not easy, because although it was already clear in her mind that she planned to erect it in the large nature reserve she owned in the eastern Netherlands, the Hoge Veluwe, she had to cancel it in 1921, when the family business was on the brink of bankruptcy. A period of crisis that did not, however, prevent her from circulating Vincent’s paintings in European exhibitions but also in the United States, until she was able to achieve it thanks to the participation of the Dutch state. In 1938 what seemed a utopia became a reality: Hellene herself became its director.

And it is from this museum that the more than 50 works proposed for the Van Gogh exhibition at the Palazzo Bonaparte in Piazza Venezia, curated by Maria Teresa Benedetti and Francesca Villanti, come.

Opened in October, the exhibition has been extended until May 7 due to the incessant flow of public that imposes long lines and a lot of waiting patience, despite the extended hours until midnight.

The tour begins with six masterpieces from the Dutch collection, born in different eras, signed by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Henri Fantin-Latour, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Floris Verster, Paul Gauguin and Pablo Picasso. Masterpieces that announce the steps of the genius, almost unknown before his tragic end. This is followed by the 4 sections devoted to Vincent’s production: divided between the Netherlands, Paris, Arles, finally,-Saint-Rémy-de-Provence and Auvers-sur-Oise.

Soft, heartbreaking lights accompany, between two floors of the building, the torment of Van Gogh’s crossing over the planet Earth, folded as he was in his own inner dimension: even the schoolchildren accompanied by the guide to discover details of his paintings remain fascinated by an artistic itinerary that turns to madness, starting from the darkness of a self-taught man attentive to the everyday life of workers (hoesmen, sowers plowers of both sexes, here is what I must draw all the time, he wrote to his brother Theo. I must observe and draw everything that belongs to country life…) to finally reach a dazzling explosion of color from his staying in Paris on until his suicide. But the human figure never leaves his painting.

How wrong is the man who does not consider himself small, who does not realize that he is but an atom. That he felt this way was well understood to him from his life spent in a family where he thought of himself as an outcast by his father in particular who did not accept the totalizing dimension of faith perceived by Vincent. There is such a revulsion in the house toward me, as if a big shaggy dog came in. Maybe it would come into the room with wet paws – and then it’s so shaggy. It will bother everyone. And he barks so loud.

His is a loneliness dilated in the space of days and meets ideally, in one room of the exhibition, that of one of the greatest protagonists of twentieth-century Italian art, Antonio Ligabue (Zurich, December 18, 1899 – Gualtieri, May 27, 1965 ), also lost in the fragility of his own existence: an exciting comparison between self-portraits of two spiritually and technically distant people, united, however, by the need to reproduce their own image in an almost obsessive way, in a world that relegated them to the margins.

Holland, Antwerp where he studied the grandeur of Rubens, France. But also London (more exactly Ramsgate). Vincent observes, travels, walks. In the continuing search for a modern sense of color, from nervous to softer brushstrokes. Illuminating was his Parisian encounter in 1886 with the Impressionists and especially the pointillists, Signac and Seraut, who painted through a chromatic decomposition into small dots.

Art is a complex process, an enormous suffering. Vincent is stubborn and unaccustomed to submission. He pursues himself, and goes beyond the Paris experience. Here is Arles, with the countryside and the yellow house where he invites his friend Paul Gaugin. But relations between the two are torn. According to Gaugin’s version, Vincent tries to hit him with a razor, and he backs away frightened. With that sharp blade, Van Gogh cuts off part of his left ear.

He works with intensity even when he decides on his own to enter the asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence but hallucinations are lurking and all he has left is painting to express the sadness of his last hours reconstructed through paintings lined up in the intense atmosphere of the Bonaparte Palace.

And Vincent is also holding the hand of the writer of this art chronicle the next day, just a few steps away from the National Archaeological Museum, in the 17th-century church of San Potito in Naples, where, to celebrate the 170th anniversary of Van Gogh’s birth, just as in the capital, Van Gogh: the immersive experience is on until April 30.

A magnificent virtual reality that has already enchanted visitors in Belgium (Brussels), China (Beijing and Hanghzou), Israel, England (London, York and Leicester), the United States (New York and Washington) and equally the Neapolitans in the version presented last year at Palazzo Fondi and now expanded in the structure that belonged to the Benedictine nuns.

Mothers with children, young couples, teenagers, students: it’s a continuous coming and going on reservation. Before being overwhelmed by the emotions projected on the walls amid music and the voice of a Van Gogh redivivivus with a British accent who evokes phrases from his correspondence with Theo, a documentary illustrates the outsider Van Gogh while in another corner of the exhibition the room in Arles that he himself immortalized in the 1888 oil on canvas and taken up in other variants reappears faithfully reconstructed, a symbol of a place protected from external turbulence.

A storm of art to be absorbed wide-eyed on lounge chairs, benches and soft cushions: the sunflowers, the starry night, the wheat field with crows, the purple-hued iris blossoms and his face bouncing in a tight rhythm all around. The audience is enraptured by a whirlwind of visions.

On the way out many notes from the public to tell about the hours spent with the artist. One over all sums up the enthusiasm in 5 words: Van Gogh I love you. Confirming the prophetic thought of Camille Pissarro, one of the greatest exponents of Impressionism: He will either go mad, or leave the Impressionists far behind. Whether he will do both I am unable to foresee.